You’d have thought they’d have learned from losing the browser monopoly they had 15 years ago due to complacency

You’d have thought they’d have learned from losing the browser monopoly they had 15 years ago due to complacency

99% of their “innovation” comes from pubic sector academia or stuff NASA already figured out anyway.

IMO SpaceX shouldn’t have exclusive rights to any of it, really

The only thing they’re really bringing to the table is money. NASA could be doing exactly the same stuff if the government actually treated it as a priority.

I say this all as someone who often supports the greens in my own country:

If they are even entertaining the idea of Harris losing being a positive for them, they are as deranged as Trump.

Trump gets in, we might as well start building bunkers, because climate change will accelerate under him, and these next 5 years are probably the most important if we’re going to stand any chance of turning this around.

I don’t know who still needs to see this, but: Voting Green in this election is the most environmentally damaging thing you can do aside from directly voting for trump.

If you vote green in this election, you will be directly responsible for everything that follows should Harris lose.

Well I’m glad someone has done this so everyone else can see for sure that this is a dead idea

That thumbnail lol

Do you guys have any kind of laws around political messaging?

This would be prison time in most functioning countries

I just love how much it must be hurting him to see his initials attached to a worthless share price

Putting everything else aside:

Why do they think they have any right to be platformed by Google, a private American company?

Can I demand that anti Putin content be platformed on VK or they have to pay me genuinely absurd fines?

I think that would categorically be world war at that point. I was more going on about seriously denouncing this kind of thing as being on the road to world war, before we get to that point

So when do we start seriously saying this is looking like we’re escalating into world war here?

In a roundabout way yes I think it is

Petrochemical companies are lobbying hard with politicians able to be bought because science is basically suggesting we essentially kill the entire industry off as expediently as possible—they are doing anything they can to stave that off for as long as they can, and they have a shitload of money to use on that goal.

If a politician can be bought, particularly over something as urgent as climate change, they are clearly going to value personal success over collective success—which pretty much always leads to right-wing authoritarianism.

Right-wing authoritarians are very good at propagandising rubes who don’t pay enough attention to the big picture when they’ve got the funds to do so.

And here we are with the current situation.

And people will be going to prison for this, right? Ballot boxes will have definitely been put in view of CCTV, right?

The Washington Post already carries a perception of bias for the Republican party, a Harris endorsement would have potentially balanced that somewhat.

This statement doesn’t even stand up to the flimsiest scrutiny

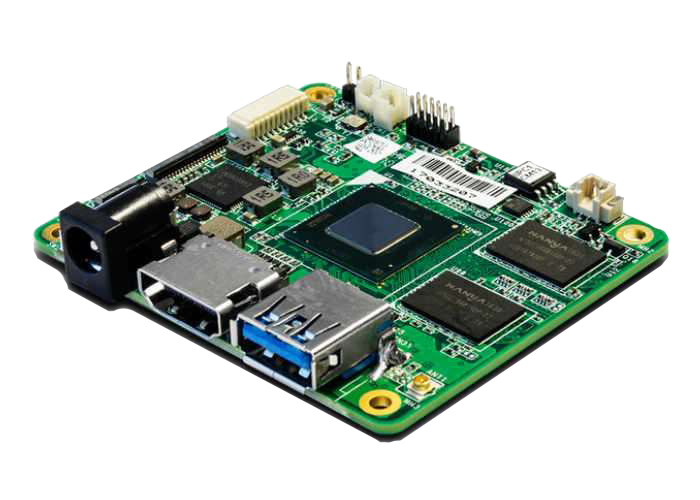

Now I have the sudden urge to build a little cluster of these despite not actually having a use case for one

It’s funny, I’m not even expecting the “everything right-wingers complain about is projection” rule to not apply at this point, but it’s getting to the point where I’m not sure if they do anything else at all

I have a voice in my role, but I’m not going to pretend I’m the only person at the company.

I’m more making the point that your single voice will not be sufficient to affect direction regarding cloud provider choice in a big enough company, that dice was probably already rolled a decade ago. I’m not saying it’s impossible or anything, but you’re gonna need to come up with an incredible business case for throwing away years of hundreds of engineers’ work building on top of platform A for a costly switch to platform B all for no customer benefit.

Now vice had its problems, but how the fuck was this goon one of the co-founders?

History tells me that if the US is disenfranchising a group of people, it’s usually racism

That mentality only works in the “adopting cloud” stage. Vendor lock-in is real, and AWS was doing what it does long before there even were competitors, let alone ones with feature parity.

If you start a job somewhere of any reasonable size with incumbent AWS infrastructure, switching to another provider will be an uphill struggle in the best possible circumstance and in most cases it will be a Sisyphean exercise that’ll probably end up with you out of a job before the AWS bill goes down

Okay cool, but what about the games you’ve already had out for like a year?

Like, idk, ff7r2 on PC?